From Plot to Plate

“There’s a reason why tomatoes represent the best of summer: fat and sensual, like biting into a tiny beam of juicy red sunlight cooled in a stream.”

EDMOND MANNING

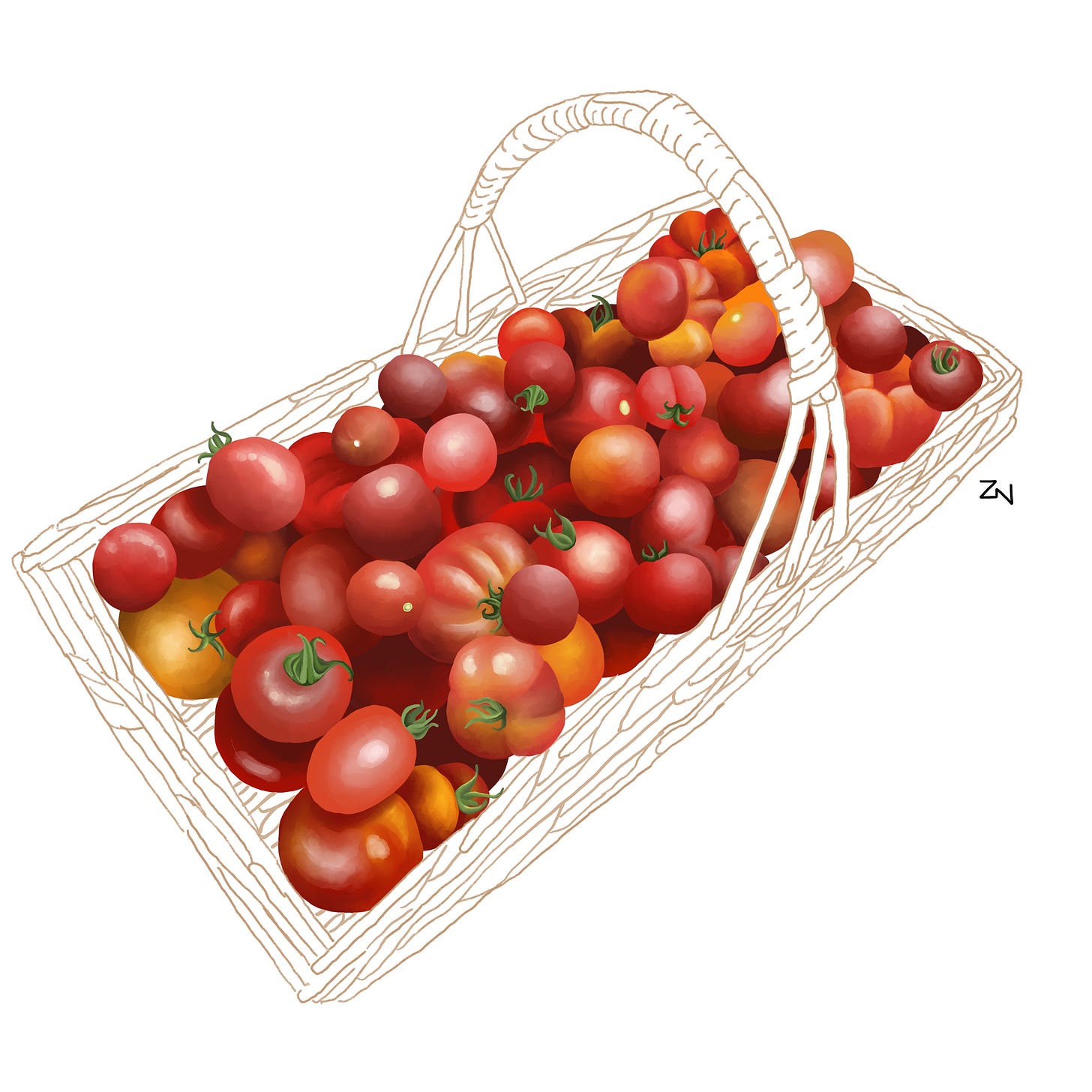

Throughout late August and into September, we’ve been harvesting masses of tomatoes from our allotment, often a carrier bag full of them each week, 2-3 bags on the occasional times we missed a weekend by being away.

We take them home and empty each bag into the kitchen sink for a good wash, then they get their calyxes removed (that’s the green leafy bit) and are roughly chopped up, discarding any bits of blossom-end-rot in the process. We have a chopping board each, with a bowl between us for the discarded parts for the compost heap, and the pan from the pressure cooker is slowly filled to the brim with the good parts. Tomato juice and seeds go everywhere; we both somehow end up with juice up to our elbows, and the seeds will be found weeks later in every crevice of the kitchen.

The pan goes onto a low heat while we clean up, and as they break down and cook, they turn into a bubbling mass of red molten liquid. At this point, I use a hand blender to blitz them into a sauce, and skim off the orange foam that gathers on top. Cleaned jars are put into a low oven to sterilise for 10 minutes, then, while they’re still hot, the tomato sauce gets ladled into them, the lids carefully screwed on tight, and the jars wiped clean of any splatters of sauce.

We then get the joy of sitting with a well-earned beer and listening out for the popping of the lids as they seal.

So far this year we have filled 26 largish jars, which should easily see us through until this time next year. They get used for everything from classic Spag-Bol to curries and Middle Eastern style tagines. It’s not like we can’t buy canned tomatoes or pasta sauces easily enough, but we genuinely love this annual routine, I love growing the tomatoes, and the taste is far superior. I have tried other methods before (I know some people like to roast theirs) including skinning and removing the seeds, but it’s too much hassle, and I think you end up removing so much goodness. I add nothing extra to them, no seasoning nor herbs, I usually reason that you can add those things when you come to use them.

We’ve been growing food on our allotment for 18 years now, and it has been a huge learning curve, not only in terms of gardening skills, but also in getting creative in the kitchen with recipes, and learning how to preserve and store the produce we have lovingly grown. We’ve pretty much perfected the annual tomato ritual now, but also discovered the best ways of dealing with all the major harvests that happen in one go, such as potatoes, onions and garlic.

My favourite vegetables (to grow) are those that politely wait to be harvested for whenever you need them, and so generally don’t need preserving or storing. The leeks, carrots and parsnips, the Cavalo Nero kale and perpetual spinach. To a degree, beetroot (it does eventually get too woody) and spring onions, even if they become bulbous mini onions. Winter squashes will ripen and then harden after harvest, so you just need somewhere cool and dry to store them.

The less patient veg refuse to hang about and need dealing with before they go to seed or become a glut. Courgettes being the major one, but also cucumbers, who often come all at once and are tricky to preserve (I have tried pickling them before you dive into the comments). Also lettuce, I find, are a crop that are suddenly all ready to harvest at the same time (week) and are impossible to keep fresh en masse. This is despite my attempts - every year - to succession sow it.

I have jammed and jellied, and chutneyed in the past. I have filled endless pickling jars. I have experimented (not always successfully) with dehydrating and fermenting. I have found numerous ways of adding vegetables to cakes and breads. I have used courgettes every which way, I don’t think there’s a courgette recipe you could give me that I haven’t tried. I have made various alcoholic concoctions, infused oils and vinegars, made ketchup and sauces, and copious amounts of soup in many combinations of varieties. I also now know how to successfully freeze pretty much any fruit or vegetable, and I can tell you which ones won’t succeed (cucumbers).

I’m not trying to boast here, it’s just an example of what us home growers learn to do over time, through sheer necessity.

The decision of what to cook for dinner, often starts with whatever we are harvesting fresh from the allotment, or what gluts need using up most. It’s not simply a case of not wanting to waste food that you’ve got to hand, but not wasting the fruits of your labour over the past months. When you’ve put all that effort into sowing, transplanting, weeding and tending to something, you make every effort to use it well. In the case of gluts, this often means researching new recipes, and trying out new methods. A vegetable you’ve never cooked before, let alone grown, becomes a whole new exciting challenge.

It feels like a major triumph when a meal contains more than three homegrown ingredients, such as a big pot of veggie chilli with tomatoes, onions, garlic, courgettes, chillies and sometimes freshly podded white beans. The more veg I can get into a single meal, the higher the level of smug satisfaction.

I don’t think I appreciated when I took on an allotment, how much I would develop my culinary skills as much as my gardening ones. Or how it would force me to think creatively and experiment so much more. It’s been challenging at times, but so much fun, and it changes each and every year.

If you’d like to support my work you can buy me a coffee here which will be very much appreciated. I also have a shop on Etsy called Zoe’s Garden Prints that you might like to mooch through, or you can share this post, which will help too. Thanks!